- Home

- Robert Goddard

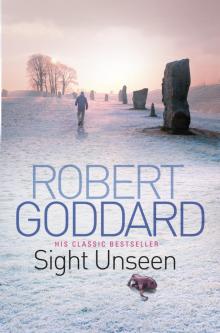

Sight Unseen

Sight Unseen Read online

About the Book

It is a hot summer’s day in the tourist village of Avebury. A man sits outside the Red Lion pub, waiting. He sees a woman with three young children, two of them running ahead while their sister dawdles behind. A child’s voice catches on the breeze.

For want of anything more interesting to do, the man watches. He sees nothing sinister or threatening. Even when another figure enters his field of vision, he does not react. The figure is ordinary – male, short-haired, stockily built. But he is moving fast, at a loping run.

And then it happens. In one swift movement, the running man grabs the youngest child and carries her away. Still the man outside the pub does not react. Suddenly, awhite transit van bursts into view, its engine racing, its rear door slamming shut. The child and her abductor are inside. The child’s sister rushes forward. The man outside the pub jumps up …

The tragedy begins at Avebury. But it does not end there.

Contents

Cover

About the Book

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Epilogue

Author’s Note

About the Author

Also by Robert Goddard

Copyright

SIGHT

UNSEEN

Robert Goddard

For the real Claire Wheatley

PROLOGUE

It begins at Avebury, in the late July of a cool, wet summer turned suddenly warm and dry. The Marlborough Downs shimmer in a haze of unfamiliar heat. Skylarks sing in the breezeless air above the sheep-cropped turf. The sun burns high and brazen. And the stones stand, lichened and eroded, sentinels over nearly five thousand years of history.

It begins, then, in a place whose origins and purposes are obscured by antiquity. Why Neolithic henge-builders should have devoted so much time and effort to constructing a great ramparted stone circle at Avebury, as well as a huge artificial hill less than a mile away, at Silbury, is as unknown as it is unknowable.

It begins, therefore, in a landscape where the unexplained and the inexplicable lie still and close, where man-made markers of a remote past mock the set and ordered world that is merely the flickering, fast-fleeing present.

* * *

Saxon settlers gave Avebury its modern name a millennium and a half ago. They founded a village within its protective ditch and bank. Over the centuries, as the village grew, many of the stones were moved or buried. Later, they were used as building material, the ditch as a rubbish-dump. The henge withered.

Then, in the 1930s, came Alexander Keiller, the marmalade millionaire and amateur archaeologist. He bought up and demolished half the village, raised the stones, cleared the ditch, restored the circle. The clock was turned back. The National Trust moved in. The henge flourished anew – a monument and a mystery.

Nearly forty years have passed since the Trust’s purchase of Keiller’s land holdings at Avebury. The renovated circle basks unmolested in the heat of a summer’s day. A kestrel, soaring high above on a thermal, has a perfect view of the banked circumference of the henge, quartered by builders of later generations. The High Street of the surviving village runs west–east along one diameter, crossing the north–south route of the Swindon to Devizes road close to the centre of the circle. East of this junction, the buildings peter out as the effects of Keiller’s demolition work become more apparent. Green Street, the lane is aptly called, dwindling as it leaves the circle and winds on towards the downs.

As it passes through the village, the main road performs a zigzag, the north-western angle of which is occupied by the thatched and limewashed Red Lion Inn. East of the inn, on the other side of the road, are the fenced-off remains of an inner circle known as the Cove – two stones, one tall and slender, the other squat and rounded, referred to locally as Adam and Eve. There is a gate in the fence, opposite the pub car park, and another gate in Green Street, on the other side of Silbury House, a four-square corner property that formerly served as the residence of Avebury’s Nonconformist minister.

It is a little after noon on this last Monday of July, 1981. Custom is sparse at the Red Lion and visitors to the henge are few. When the traffic noise ebbs, as it periodically does, somnolence prevails. There is a stillness in the air and in the scene. But it is not the stillness of expectancy. There is no hint, no harbinger, of what is about to occur.

At one of the outdoor tables in front of the Red Lion, a solitary drinker sits cradling a beer glass. He is a slim, dark-haired man in his mid-twenties, dressed in blue jeans and a pale, open-necked shirt rolled up at the elbows. Beside him, on the table, lie a spiral-bound notebook and a ballpoint pen. He is gazing vacantly ahead of him, across the road, towards the remaining stones of the southern inner circle. They do not command his attention, however, as a glance at his wristwatch reveals. He is waiting for something, or someone. He takes a slurp of beer and sets the glass down on the table. It is nearly empty. Sunlight glistens on the swirling residue.

A child’s voice catches his ear, drifting across from the Cove. There is, at this moment, no traffic to mask the sound. The man turns and looks. He sees a woman and three children approaching the Cove from the direction of the perimeter bank. Two of the children are running ahead, racing, perhaps, to be first to the stones: a boy and a girl. The boy is nine or ten, dressed in baseball boots, blue jeans and a red T-shirt. The girl is a couple of years younger. She is wearing sandals, white socks and a blue and white polka-dot dress. Both have fair hair that appears blond in the sunshine, cut short on the boy but worn long, in a ponytail, by the girl. The woman is lagging well behind, her pace set by the youngest child, toddling at her side. This child, a girl, is wearing grey dungarees over a striped T-shirt. There can hardly be any doubt, given the colour of her hair, tied in bunches with pink ribbon, that she is the sister of the other two children.

It is much less likely that the woman escorting her is their mother. She appears too young for the role, slim, fine-featured and dark-haired, surely not beyond her early twenties. She is dressed in cream linen trousers and a pink blouse and is carrying a straw hat. Her attention is fixed largely on the little girl beside her. The other two children are dashing ahead.

As they approach the stones, a figure steps out from the gap between Adam and Eve, hidden till then from view. He is a short, tubby man in hiking boots, brown shorts, check shirt and some kind of multi-pocketed fisherman’s waistcoat. He is round-faced, balding and bespectacled, aged anything between thirty-five and fifty. The two children stop and stare at him. He says something. The boy replies and moves forward.

T

he man outside the Red Lion watches for lack of anything more interesting to watch. He sees nothing sinister or threatening. What he does see is a flash of sunlight on glass as the man by the stones takes something out of one of his numerous pockets. The boy steps closer.

The woman is hurrying to join them now, not running, nor even necessarily alarmed, but cautious perhaps, her attention suddenly diverted from the slow-moving infant who follows at her own dawdling pace, before abruptly sitting down on the grass to inspect a patch of buttercups.

The man outside the Red Lion sees all of this and makes nothing of it. Even when another figure enters his field of vision from behind Silbury House, he does not react. The figure is male, short-haired and stockily built. He is wearing Army surplus clothes and is moving fast, at a loping run, across the stretch of grass beyond the stones. The woman, who cannot see him moving behind her, is smiling now and talking to the man in the fisherman’s waistcoat.

And then it happens. The running man stops and bends over, grasps the seated child beneath her arms, lifts her up as if she weighs little more than the buttercup in her left hand and races back with her the way he came.

The man in the fisherman’s waistcoat is first to respond. He says something to the woman, raising his voice and pointing. She turns and looks. She puts her hand to her mouth. She drops her hat and begins running after the man who has grabbed the child. Screened as he is by Silbury House, he can no longer be seen by the man outside the Red Lion. The roaring passage of a southbound lorry further confuses the senses. Everything is happening very quickly and very slowly. The beer-drinker does no more than rise from his seat and gape as the next minute’s events spray their poison over all who witness them.

A white Transit van bursts into view round the corner from Green Street, its engine racing, its rear door slamming shut. The child and her abductor are inside. That is understood by all, or intuited, for only the woman has seen them scramble aboard. A second man is driving the van. That is also understood, though no-one catches so much as a glimpse of him amidst what follows.

The man in the fisherman’s waistcoat has taken a few ineffectual strides after the woman, but has now turned back. The boy is standing stock-still between Adam and Eve, paralysed by an inability to decide what to do or who to follow.

No such indecision grips his sister, though. She is running, ponytail flying, towards the gate onto the main road. What is in her mind is uncertain. From where she was standing, she will have seen the van pull away. She knows her sister is being stolen from her. She is not equipped to prevent the theft, yet she seems determined to try. She flicks up the latch on the gate and darts through.

The van turns right onto the main road. A northbound car, slowing for the bend, brakes sharply to avoid a collision and blares its horn. The driver of the van pays this no heed as he accelerates through a skid, narrowly avoiding the boundary wall of the pub car park.

The girl does not pause at the edge of the road. She runs forward, into the path of the van. She turns towards it and raises her hands, as if commanding it to stop. There is probably just enough time for the driver to respond. But he does not. The van surges on. The girl holds her ground. In a breathless fraction of a second, the gap between them closes.

There is a loud thump as hard steel hits soft flesh. There is a blurred parabola through the air of the girl’s frail, flying body. There is the speeding white flank of the van and the slower-moving dark green roofline of the following car. Neither vehicle stops. The car driver proceeds as if he has seen nothing. And maybe he has somehow failed to register what has occurred. He does not have to swerve to avoid the crumpled shape at the side of the road. He simply carries on.

The van and the car vanish round the next bend in the road. All movement ceases. All sound dies.

It is only for a second. Soon everyone will be running. The boy will be crying. The woman will be screaming. The man who was drinking outside the Red Lion will be hopping over the wall of the car park, his eyes fixed on the place at the foot of the opposite verge where the girl lies, her blue and white dress stained bright red, the tarmac beneath her darkening as a pool of blood spreads across the road. And her eyes will seem to meet his. And to hold them in her sightless gaze.

But that is not yet. That is not this second. That is the future, a future forged in the stillness and the silence of this frozen moment.

It begins at Avebury. But it does not end there.

ONE

IT HAD BEEN a fickle winter in Prague. Yet another mild spell had been cut short by a plunge back into snow and ice. When David Umber had agreed to stand in as a Jolly Brolly tour guide for the following Friday, he had not reckoned on wind chill of well below zero, slippery pavements and slush-filled gutters. But those were the conditions. And Jolly Brolly never cancelled.

Umber’s exit from the apartment block on Sokolovská that morning was accordingly far from eager. A lean, melancholy man in his late forties, his dark hair shot with grey, his eyes downcast, his brow furrowed with unconsoling thoughts, he turned up the collar of his coat and headed for the tram stop, glancing along the street to see if he needed to hurry.

He did not. There was no tram in sight, giving him a chance to examine the letter he had found in his mailbox on the way out. Deducing from the typeface visible through the envelope-window that it was in fact a bank statement, he thrust it back into his pocket unopened and pressed on to the tram stop.

God, it was cold. Not for the first time when such weather prevailed, he silently asked himself, ‘What am I doing here?’

The answer, he knew, was best not dwelt upon. He had stayed on after the end of his teaching contract last summer because of Milena. But Milena had gone. And so had the temporary post he had found for the autumn term. He had a small circle of friends and acquaintances in Prague, happily including Ivana, Jolly Brolly coordinator and entrepreneuse manquée. But he also had plenty of evidence to strengthen his sense of drift and purposelessness.

He stood at the stop, shifting from foot to foot in an effort to keep warm, or at least to avoid getting any colder. The heating in his apartment block was in dire need of an overhaul. That could in fact be said of pretty much everything in the block. He had moved there as a stopgap measure when his much more salubrious and ironically cheaper flat near Grand Priory Square had vanished under the waters of the Vltava during the cataclysmic flood of August 2002. He had been in England at the time, but virtually all his possessions had been in the flat. The flood had claimed those tangible reminders of his past, leaving a void in his sense of himself that the sixteen months since had failed to fill.

The red and white nose of a tram appeared through the murk. Those waiting at the stop shuffled forward, some of them taking last drags on their cigarettes before flicking the butts into the slush. Umber squinted towards the tram, struggling to read its route number. It was a 24. Well, that was something. If it had been an 8, he would have had to stand there for another bone-chilling few minutes.

The number 24 pulled up and the passengers piled aboard, Umber hopping onto the second car, where there were more vacant seats. He slumped down in one and closed his eyes for a restful few moments as the tram started away. As a result, he did not notice the short, barrel-chested man muffled up in parka, gloves, scarf and woolly-hat who jumped on just as the doors were closing. He had no cause to be on his guard, after all. A Prague tram at the back end of winter was hardly where he would have expected the past to creep up on him. He was not thinking about any of that.

But then he did not need to. David Umber’s past was of an order that did not allow for genuine forgetting. It was not necessary to apply his mind to it consciously. It was simply there, always, pulling him back, dragging him down. It would never leave him. All he could do was refine his tactics of evasion. And this, he knew but did not care to admit, was why he had stayed on in Prague. It was a refuge, a hiding-place. It was far from anywhere tainted by all that he did not wish to recall. But it was not, he was to di

scover before the day was out, far enough.

The tram trundled on through the streets, picking up more passengers than it shed, so that by the time it reached Wenceslas Square it was crammed. Umber got off with a mob of others and headed for the Wenceslas Monument in front of the National Museum. That was the appointed meeting-place for those hapless tourists who had decided to spend a thousand koruna on a six-hour walking tour of the city’s principal attractions, with lunch thrown in, in the care of an old Prague hand replete with local lore. (Jolly Brolly never knowingly undersold itself.)

About a dozen tourists were waiting by the statue of Bohemia’s patron saint. The cold weather had taken its toll on numbers, for which Umber was grateful. He would not have to shout to make himself heard by such a small group. They were the usual mix of ages and nationalities, clutching their polyglot of guidebooks. Ivana was in the process of unburdening them of their cash. She acknowledged Umber’s arrival with a relieved smile.

‘You’re late,’ she whispered as she handed him his staff of office – a rainbow-patterned umbrella.

‘Je mi líto,’ he replied, apologizing being one of the few aspects of Czech he had mastered. ‘I overslept.’

Ivana’s smile stiffened only slightly as she set about introducing him to his charges. A doctor of history, she called him, in order to forestall any complaints about his clearly not having been born and bred in Prague. It was not a technically valid description. Umber had never finished his doctorate. But, in another sense, which afforded him some wry amusement, it was true. There would be a little doctoring of history before the tour was over. He could guarantee that.

There was one latecomer who settled up with Ivana after she had said her preliminary piece. Having failed to register the man’s presence on the tram, Umber naturally made nothing of his last-minute arrival. Ivana wished them a good day and bustled off to the bank with the takings. She would soon be back in the warmth and relative comfort of the Jolly Brolly office. A phone call to Janoušek, proprietor of U Modré Merunky, where they were scheduled to stop for a ‘typical delicious Czech lunch’, and her duties would be concluded.

The Fine Art of Invisible Detection

The Fine Art of Invisible Detection One False Move

One False Move Panic Room

Panic Room Beyond Recall

Beyond Recall Out of the Sun

Out of the Sun In Pale Battalions - Retail

In Pale Battalions - Retail Painting The Darkness - Retail

Painting The Darkness - Retail The Corners of the Globe

The Corners of the Globe Name To a Face

Name To a Face Closed Circle

Closed Circle Caught In the Light

Caught In the Light Into the Blue

Into the Blue Past Caring - Retail

Past Caring - Retail Past Caring

Past Caring Hand In Glove - Retail

Hand In Glove - Retail Borrowed Time

Borrowed Time Days Without Number

Days Without Number James Maxted 03 The Ends of the Earth

James Maxted 03 The Ends of the Earth Fault Line - Retail

Fault Line - Retail Play to the End

Play to the End Sea Change

Sea Change Never Go Back

Never Go Back Take No Farewell - Retail

Take No Farewell - Retail Blood Count

Blood Count Found Wanting

Found Wanting Sight Unseen

Sight Unseen Hand in Glove

Hand in Glove The Ways of the World

The Ways of the World